av Eric Alagan

377

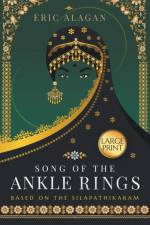

In classical Tamil, Senkonmai means Righteous Sceptre. In latter centuries it became senmai, or when shortened even further-sen. Kol is the wooden rod used by a shepherd to guide and protect his flock. Combine the two words, and senkol (a word in popular use) becomes the staff (sceptre) a king wields. It is the physical manifestation of austerity, purity, mercy, and truthfulness-the dharmic tenets that guided the rulers of ancient Tamilakam. The sceptre was not a symbol of lordship and power, as was commonly associated with the royal mace in other ancient cultures such as the Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Persian, and even later-day monarchies.In ancient Tamilakam, kings were known as kovalan and kavalan, both terms used interchangeably. Kovalan is the wielder of the senkol. Kavalan is the servant-guardian.A kovalan, by his example, serves and guards and guides the state.If he fails in this duty, he must make good, or if unable to rectify the error, he must pay a penalty. The price could be restitution, such as money to put matters right or some other favour that restores or compensates the damage or loss to the affected constituent, be it a person or an institution. In extreme cases, he must be prepared to forfeit his life. Honour, duty, and accountability demanded this of him.The senkol in the hands of the kovalan constantly reminded him he, as the wielder of the kol, was a mere kavalan, servant-guardian of the state.These obligations on the king were disseminated to the people by temple inscriptions, palm-leaf books, guru-sishyan (teacher-student) discourses, and history enacted through the medium of story-telling (oral tradition), visual arts (portraiture and sculpture), and performance arts (dance and drama).An early example of the kavalan's duty, responsibility, and accountability was expounded in Silapathikaram, the classic Tamil epic composed by Elango-Adigal (the venerable ascetic prince). He was a prince-turned-monk and brother of Senkuttuvan, the Cheran king.Song of the Ankle Rings is based on the Silapathikaram.The Pandyan King, Nedun-Cheliyan, wrongly condemns Kannagi's husband of stealing the queen's anklet, and puts him to death. When she learns of this atrocity, she confronts the king in open court and proves her husband's innocence.The righteous king, horrified by his negligence that had led to the irredeemable error, grabs his chest and cries, "Am I king? No, I am the thief."Distraught and ashamed of the gross injustice committed, he digs his fingers into his chest and dies-his heart having failed him.Panegyrists sang his praises thus: "The kavalan's injustice bent his senkol, yet the kovalan's death reinstated his dynasty's righteousness. Rejoice people, for the senkol stands upright again."Kannagi, arguably the first female protagonist in Tamil literature, is revered in India and the Tamil diaspora as an exemplary model for womanhood. There are temples and statues raised to her memory.Welcome! Hear Kannagi and her husband, Kovalan-his name is an irony in more ways than one-recount their stories in Song of the Ankle Rings.