av Gilbert Sorrentino

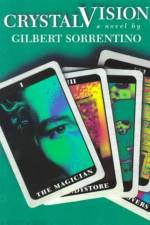

146

The Tarot deck as read from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, circa the late Forties and early Fifties. A candy-store (or bar or street corner) symposium on life, love, and storytelling. An eruption of local voices approaching Dantean - but hilarious - clamor. A display of inventiveness whose sneaky expanses depend on non sequiturs that Woody Allen would envy, on satires of flowery style. A companion-piece to Steelwork (1970). Yes, Sorrentino's new novel is all these things, and one thing more, which gives its title a justification beyond all the laughs: a closely woven examination of symbols - with the proposition that they are actually fateful choices; either that or judgments. Calvino's likewise Tarot-based The Castle of Crossed Destinies shares similar concerns, but Calvino is nowhere the irrepressible vaudevillian that Sorrentino is. Trotted out here, while drinking Mission cream sodas, eating Mrs. Wagner's pies and root beer barrels, waiting for the early Mirror, are such neighborhood luminaries as: aspiring litterateur Richie; acneous Big Duck; The Arab, master of baroque malapropisms; Professor Kooba; Santo Tuccio the movie buff; Fat Frankie; Little Mickey; Cheech; and The Drummer. Each has a story to tell (and overrule) each other, and all of them ere under the ultimate spell of an elusive symbolic character called "the Magician" - who, this being Sorrentino, is as hapless as the guys in the candy-store. (Magically arranging for an angel-with-trumpet to appear on a gas-station wall during a war-time night of free movies, the Magician can't, however, get the angel to make a sound, having neglected to make an angel that knows how to play a horn.) The comedy is marvelously broad throughout - especially when The Arab offers his just-slightly-off disquisitions: "I despise and abbhorate the baseball. . . . And akinly, all sporting ventures. Save the racing ovals and their equine contests which oft are of a spectaculous beauty"; or "It nudges and bunks into the tragic that you did not consider gleaning this information, Billy." And set-pieces (a Sorrentino specialty) are here in force and quality: a declasse gossip column, a list of old-time Brooklyn candies, a Hungarian folk tale. But under all the laughs and exuberant polyphony, Sorrentino does an extremely crafty thing: he makes these sweet slobs bear the task of explaining symbol and illusion. ("A wedge of pie then. Suppose you have it and that it stands for a triangle. Suddenly, Big Duck, let's say, comes along, his acne is goddamn growling. And he stuffs the pie into his mouth. What about that?") Never merely the maker of high-modernist yet rude entertainments, Sorrentino also always strives to produce literary correctives. And rarely has he done the job so well, so radically, so comically as in this fluorescent, subtly amalgamated book - one of his best. (Kirkus Reviews)