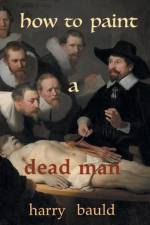

av Harry Bauld

237

A lyric leap forward from Harry Bauld's playful and passionate debut, The Uncorrected Eye, How to Paint a Dead Man peers so intensely at art that the verse becomes somehow both hallucinatory and colloquial at the same time. The new collection leaves aside the formal dance of some of the earlier work but extends the vivid and often comic explorations of art and the American vernacular. With no-look pathos and sudden jazzy riffs, many of these poems vamp on artists from Renaissance how-to author Cennino Cennini through Canaletto, Rembrandt, Magritte, the German Expressionists, and Picasso, often through dramatic monologues; Bauld also pitches playfully through fellow writers Mark Strand and Joyce Carol Oates, among others, to tap into the turbulent spirit of the moment. "Always now / it seems we look at art and it looks back / at us on trial," as he writes in "The Eyes."One figure that looms large here belongs to 80's avatar Jean-Michel Basquiat, the former street graffiti artist who shot to world-wide fame and died of a drug overdose at twenty seven. Bauld, who spends part of the year in the Basque country and has written previously about that region's complex history, is oddly sensitive to the seemingly merely linguistic tie between Basque and Basquiat. It's the voice of a Basquiat angel in "Annunciation" who says, "You already/gave birth to this flame/you don't know the name of." The painted "dead man" of the title takes on many identities: not only the poet's father but Basquiat, Mark Strand, the victims of a mass shooting--and the shooter himself--as well as each of the artists evoked, having passed ironically under Bauld's gaze from observer to observed, painter to model, creator to subject. "Art is always saying hello and poetry is always saying goodbye," reads the Kenneth Koch inscription to the book's opening poem, the punning and satirical list, "Duals in the Old West." ("The sun is always saying shut up and the moon is always whispering tell me more....")But Bauld sets out not just to burlesque and blur but to erase these teasing but finally facile dualities. This a collection that displays, explores, and ultimately fuses all sorts of opposition: fame and obscurity, serenity and violence, inner and outer experience, what's real and what's imagined. One expects no less from a poet whose own name is an oxymoron.Still, floating above the undercurrent of death-haunted discontent and loss is also a delight-the hello of art, in Bauld's case verbal as well as visual, in the face of elegy's traditional goodbye: "It's what you do after you go down/that counts," he writes in "Self Portrait as Marco Polo as Miles Davis" about the floored boxer Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion. And in "Cadillac Moon," with a sidelong swipe at our current political scene, the poet observes a Basquiat rendering of a car: a set of fantasy wheels that play like four-square in the hands of children who, like the seven artists who will save us, plow their fingers in paint furrows to change all the colors of today's sky, rub out the authoritarian moon and everything under it, making a holy mess and moving