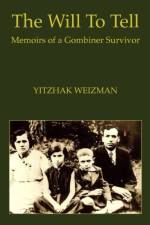

av Yitzhak Weizman

511

The story of the life of our late father Yitzhak Weizman was only revealed to us, his three children, when we were already parents to our own children.We always knew that he was a Holocaust survivor. He had the number 145227 tattooed on his arm.But he told us very little about his Holocaust experiences. "It was a long time ago," he used to say, and "Polanyah" (as we called Poland at the time) seemed very far away. We studied in school and read books about it, but the Holocaust was not present in our home. Unlike other children of survivors, we were not pressured to eat everything on our plates and were even allowed to waste food. "It will not help the children of Africa if you eat everything," used to say our mother, who came from a family that had been living in Israel for six generations. Our father smiled.What we did know was that our father's grandfather had been an important figure in his life. He was a successful industrialist and trader, one of the richest Jews in the town of Gombin. He introduced our father to the secrets of the family business, but he also wanted him to learn Judaism in the heder, the traditional school where Jewish boys received basic religious instruction. We also knew that our father participated on the youth movement Hashomer Hatzair, that he loved to play soccer, and that the horses in Gombin were fast - he used to say that the carts in Gombin, even when loaded with grain, were faster than the lazy soccer players in Israel.We were aware that our father was the only survivor of his family. His father Menachem, his mother Hannah, and his sister Helcia had all been murdered during the Holocaust. But we did not really know how he had survived. He kept us ignorant about it. The shadows of the past remained outside the door.Things changed when the grandchildren arrived. The new generation did not like to be kept ignorant about anything. They asked questions and wanted to receive answers. Our father could not resist them. Without the pressure of the grandchildren's questions, it is doubtful that this book would have ever been written.Yitzhak WeizmanviWe have read our father's story over and over again. He writes things as they were, almost like an objective bystander - avoiding hyperbole or emotional excess. With characteristic modesty, he writes: "I am not a hero and I never wanted to be a hero."We emphasize this fact because the figure of speech "like cattle to the slaughter" burned our father's soul. In the times of the establishment of the State of Israel, that expression was often used to describe the way in which the Jews had perished during the Holocaust. When the country formally adopted the wording "Shoah veGvurah" (Holocaust and Heroism) to commemorate the tragedy, the relationship between the two concepts created difficult dilemmas for the construction of a new ethos in the Jewish state.Our father's story is a story of coping. It is also a story about his disposition to discern points of light in the midst of darkness and preserve them in his mind.As the readers will see in the book, the permanent effort to cope was our father's daily reality. We believe that some of the choices he made were truly heroic. One example is the story about his involvement in what he describes as an "interesting incident" in the Jędrzejów camp. Despite his lack of experience, he volunteered to replace the damaged wheel of a German officer's vehicle. In the process, he saved his life and that of his mates. Then, when he was given extra food as a reward for replacing the wheel, he chose to share it with his friends rather than keeping it for himself.